Very few students will ever care to know how to graph a parabola, but everyone will need to know how to do their taxes. Don’t require trigonometry but require basic tax preparation.

Lindsey, 41, mixed race mother of five in Oregon suburb

Personal Finance Lab’s parent organization turns 30 this year, and we have been involved in the changing landscape of k-12 education in the United States every step of the way. I have been working on our curriculum development over the last 5 years, and during that time I’ve been travelling around the country speaking at regional education conferences, holding webinars and focus groups with teachers, diving into discussions with parents, and trying to help make sure every student in the United States had access to the basic financial literacy skills they will need after graduation.

What we do here at PersonalFinanceLab is to bring the best of what we’ve learned from the last 75 years of experiments in education reform across the country, and apply it to how we teach financial concepts in schools. Much of this comes back to an ever-evolving balance between what are known as the STEM disciplines, CTE programs, and “Life Adjustment” schools. How these three areas interact is essential to understanding how Personal Finance and Economic topics appear in the classroom.

A History Lesson

Before getting into the play between the areas of emphasis, let’s take a step back and see how we got to where we are today.

Post-Depression Education Reform

“…60 per cent of those in secondary school were neglected. The college preparatory curriculum was too remotely related to the lives they were living and were going to live; students didn’t plan to become skilled in any particular trade because the jobs open to them did not demand the kind of training schools could offer”

Carl Franzen, 1951

After World War II, high school enrollment across the United States started to surge. This is important – in 1930, high school enrollment was less than 50% of all 14-17 year olds. By 1950, it soared to over 70%.

This caused a full-blow existential crisis in schools around the country: Before 1950, most students would leave high school as soon as they could find a job – graduates who stayed through to the end were generally being groomed to continue on to college or enter a specific trade. As high school enrollment spiked, more and more students might not be on either of those paths: not planning on going to college, but also not planning to embark on a specific trade.

This caused a huge debate on education policy across the country – if more and more students were expected to graduate high school, what did society expect them to actually learn while they were there?

Life Adjustment Education

The answer was provided largely by market demand. Parents of this first spike of high school graduates themselves grew up during the Great Depression, and wanted their children to grow up knowing how to face the “Real World”. The concept of “Life Adjustment Education” developed and spread quickly from about 1947 through 1956 – the idea being that schools did not necessarily need to teach “more” subjects, but to put them through the lens of preparing students after graduation. Math classes should include lessons on taxes, English classes should include writing for business, science classes should focus on careers available in each field.

This was extremely popular among parents, who saw it as a natural “3rd path” between the College Prep and CTE curriculum, but generally speaking there was no “revolution”. Classes were still taught primarily through lecture, with fairly soft directives taken up by more ambitious teachers.

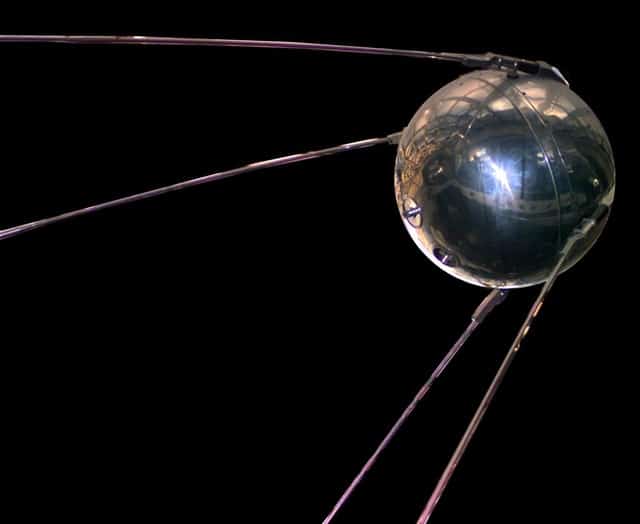

Sputnik and the STEM Crisis

The concept of Life Adjustment Education came to a screeching halt in 1957 with the launch of Sputnik. The country was gripped in panic – the “Missile Gap” was still a few years away, but the “Engineering Gap” was staring down directly from the heavens. It became a top national priority to start producing more engineers and technical specialists, as quickly as possible.

At the time, these fields broadly consisted of Biology, Chemistry, Physics, and Mathematics. The National Science Foundation pumped billions of dollars into curriculum development, teacher training, film reels (for self-taught classes while new teachers were being recruited and trained) and new ways of teaching.

The Rise of the Lab

This is where the story gets interesting – the National Science Foundation push, and the funding that followed, is the reason why every high school has a biology and chemistry lab today. The real revolution in education came about explicitly because there were a lack of qualified teachers at the time – necessity was the mother of invention. Since there was no way to get fully qualified science instructors in every classroom on the turn of a dime, a radical new method of teaching was applied – the Experiential Classroom.

The National Science Foundation’s curriculum included libraries of exercises that could be conducted in the newly-built Labs – exercises that were guided by teacher input, but relied on students working by themselves or in groups to execute a set of instructions in a dedicated lab environment. At the time, teachers simply did not have the expertise to lecture about chemistry for an hour per day, and the experiential component was to give them a break by letting students “learn by doing”.

It is hard to undersell how well this new approach worked – STEM graduates flooded universities in the years afterwards. The engineers behind the Apollo moon landings were the first generation to graduate high school from these new Labs, and American universities were well-fed with students for STEM fields for decades afterwards.

Parents were also overwhelmingly supportive – they loved seeing the physical presence of the Labs at the schools, and could tangibly identify what their kids were learning, and why. The high school science teacher even became famous in their communities (if you’ve seen Stranger Things on Netflix, you’ll notice only one teacher pops up with a speaking roll).

STEM Today

Despite news stories that you may have seen arguing otherwise, the STEM crisis has largely abated. That is not to say we don’t need STEM – but that this is a problem we’ve been throwing money at for decades, and generally seems to be under control. There are still STEM vacancies – but today we have the graduates to fill them.

So this brings is back to where we left off back in 1956 – how do we get back on track for preparing students for life after school? What do we want students to know when they graduate high school, and how do we teach them?

Academics First, But Not Alone

The American Federation of Teachers commissioned a study to answer exactly this question a couple years ago, and the answers aren’t surprising. More than half of parents agree that pure academics should definitely be at the top of the agenda in high schoool (53%) compared to just 2 percent saying high school’s main focus should be preparing students for work.

However, diving a layer deeper shows a very different story. 75% of all adults say that high schools have at least some responsibility to prepare students both academically and to teach job skills. When asked about elective classes, more parents wanted their students to take a job skills or personal finance class than any advanced mathematics (or arts and music).

This is mirrored in nation-wide trends: 20 states now require some form of financial literacy to be taught in high schools (usually combined with some other subject) – as a society, we want our students to be better prepared for life after graduation, but we don’t want to sacrifice other academics to do it.

Enter The Finance Lab

The biggest success story of the STEM push of the 1950’s and 1960’s was the High School Lab, and kick-starting the entire experiential education revolution.

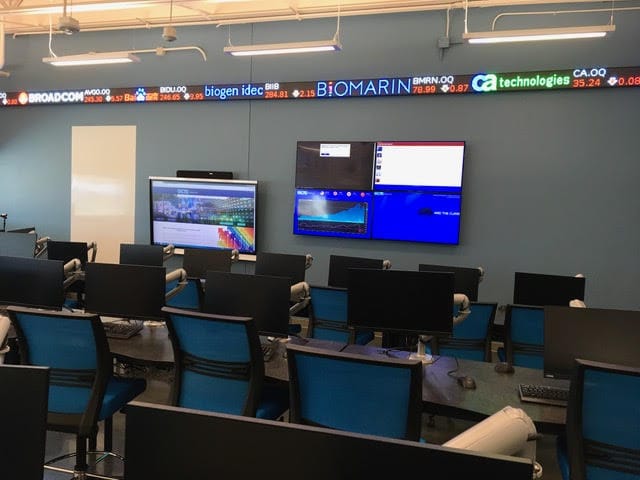

Thanks to advances in technology over the last 10 years, Financial Literacy is now the prime candidate for new Labs across the country – a dedicated place in the school focusing on learning about money, economics, budgeting, insurance, and everything in between. New simulations (like the ones we pioneer here at PersonalFinanceLab.com) turn these formerly dry topics into the most exciting place at the school, with interactive simulations, white-knuckle trading competitions, streaming market data, and life-inspired budgeting games taking center stage. This simply wasn’t possible 15 years ago, but the experimental approach has quickly proven to be the “missing piece of the puzzle” when tackling financial topics all over the country.

Math departments love labs because of a rising trend of teaching financial math classes (some states even include Personal Finance and Economics as part of their Math standards). CTE departments love them because it is the natural place to hold accounting, entrepreneurship, and business classes (and is a great way to grab student attention!). Social studies departments love them because it breaks off the lecture series and is an awesome way to introduce economic and financial topics. Teachers love them because it turns their classroom into the coolest room at the school, and parents love them for the same reason they liked the biology and chemistry labs – they have a clear, tangible way to see that their kids are learning valuable life skills in an environment explicitly designed for that purpose.

Building a Lab is usually the one thing that each of the different departments can usually agree on. Hundreds of new labs are being built across the country every year (particularly in states that have a mandate to teach financial topics). If your school doesn’t have one already, ask your administration:

We have a biology lab. We have a chemistry lab. Why not a Personal Finance or Business Lab?

Kevin Smith is the director of Curriculum Development for PersonalFinanceLab.com. He holds a Master’s degree in Economics from Concordia University in Montreal, and is a candidate for a Master’s of Public Administration from the Illinois Institute of Technology.